Art & history in PG's writing

lukehollis • 12 May 2023 •

Saying you like and study the essays of Paul Graham is as universally uninteresting as saying you like apple pie: he deservedly is as revered and a household name for every creator.

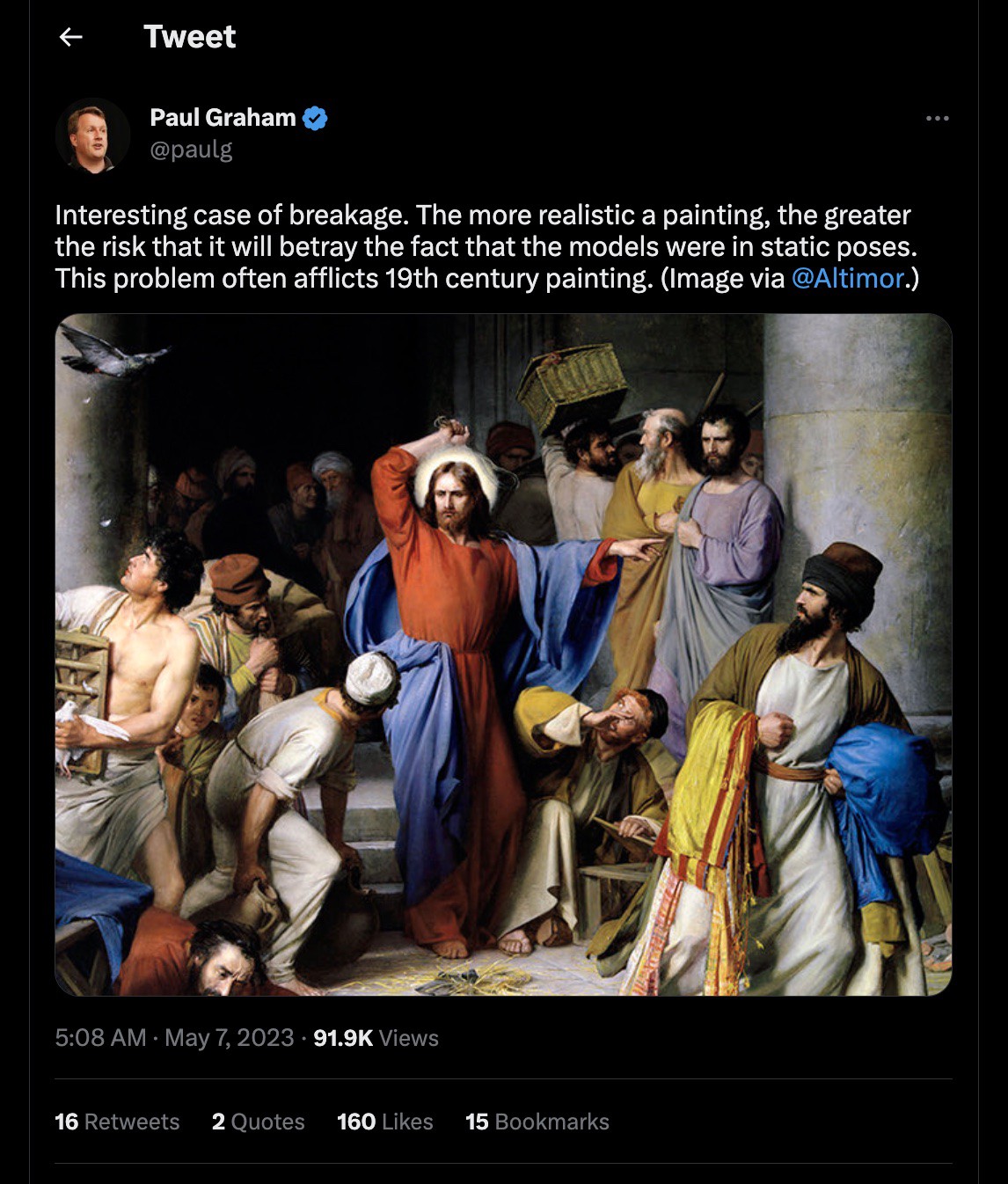

PG’s writing is informed often by history, art, and lit, and his Twitter is filled with this–more than many academics that I follow. For example, at random from his feed, this Tweet from Sunday:

This fusion of art, business, and technology is overlooked way too often as one of the sources of the brilliance of his work.

So when one indie hacker tries to defame me on Twitter by saying that I stole my last Lifelog title “Every happy indiehacker is happy in the same way, every unhappy ih is unhappy in their own way” from YC, when that quote is actually from the start of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, it gets under my skin. It probably came from PG or someone at YC that read a book–and cared about art and business both.

There’s so much that I don’t know in the world. But when I tell some people that along with studying software engineering, I studied classical art & languages, they look at me like I just confessed I had a mental disorder. PG’s posts about history & art & how they inform business & technology offer some validation for my strange choice of life, even if I have none of my own with my current sad 300usd mrr.

I love lifelog. If anyone made it this far, I hope that my entries aren’t a burden to this website or mess up its otherwise more useful content somehow.

Please don’t hate me, but this type of writing draws on the “epistolary” novel, from Latin epistola, or “letter”–but has come to mean any type of episodic account in journal entries, newspaper clippings, etc.etc.

So my lifelogs take inspiration from the epistolary work that writers and indiehackers offer as some type of apology for their weird lives–and hopefully give some sense to my own. Much moreso than being about something I believe or know.

Like Tristram Shandy from one of my previous posts, or the rambling quixotic voice of Moby Dick, which embodies the spirit of the indie hacker & builder in the call of the ocean to the sailor better than anything else I know: (super condensed version, I stopped adding ellipses)

Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball. With a philosophical flourish Cato throws himself upon his sword; I quietly take to the ship. There is nothing surprising in this. If they but knew it, almost all men in their degree, some time or other, cherish very nearly the same feelings towards the ocean with me.

… Circumambulate the city of a dreamy Sabbath afternoon. What do you see?—Posted like silent sentinels all around the town, stand thousands upon thousands of mortal men fixed in ocean reveries. Some leaning against the spiles; some seated upon the pier-heads; some looking over the bulwarks of ships from China; some high aloft in the rigging, as if striving to get a still better seaward peep. But these are all landsmen; of week days pent up in lath and plaster—tied to counters, nailed to benches, clinched to desks. How then is this? Are the green fields gone? What do they here?

But look! here come more crowds, pacing straight for the water, and seemingly bound for a dive. Strange! Nothing will content them but the extremest limit of the land. They must get just as nigh the water as they possibly can without falling in. And there they stand—miles of them—leagues. Inlanders all, they come from lanes and alleys, streets and avenues—north, east, south, and west. Yet here they all unite.

Why is almost every robust healthy boy with a robust healthy soul in him, at some time or other crazy to go to sea? Why upon your first voyage as a passenger, did you yourself feel such a mystical vibration, when first told that you and your ship were now out of sight of land? Why did the old Persians hold the sea holy? Why did the Greeks give it a separate deity, and own brother of Jove? Surely all this is not without meaning. It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life; and this is the key to it all.

He quietly takes to his ship. I clackily take to my keyboard.

Comments

@lukehollis No worries Luke. In fact, I’m rather enjoying this epistolary style. And learning something new (I tend to write in a too structured/straightforward way for my liking).

I’m glad you clarified with the guy that the true source of that quote is Tolstoy. Funny how we tend to frame our references entirely within the tech scene.

Love that you brought up art and history - the best products seem to a silent foundation in those, like how the first Macintoshes had artists working on it.

That’s super interesting about the first Macs! I had no idea. That’s fascinating.

And @therealbrandonwilson, great to know that he survived with the Latin&Greek degree–so you’re saying there’s hope…

No burden, at all. I’m glad to see you are showing up to write. My dad had degrees in Latin and Greek from Northwestern, so I always like a good classical reference.